Parisian Streets

Paris itself is a small city, less than two square miles. It’s about a mile and a half walk from the Bastille to the Tuileries Gardens, and a little less than that to walk from St. Denis or St. Martin Gate to the Sorbonne. In more modern times, it would take a pedestrian under an hour to traverse from one side of the city to the other. In King Louis XIII ’s time, however, it could take the better part of a day.

With the exception of a few avenues, Paris is still very much medieval in design. These roads don’t follow set patterns; Parisian streets are not laid out in a convenient grid nor are they easily navigable. Many streets are named differently depending on where you are and terminate in odd places. A street also shrinks and expands along its length and a visitor could be easily forgiven for not recognizing that an alley is actually a proper street.

Parisian streets are also small, as medieval streets weren’t designed to accommodate carriages (especially not to leave enough room for carriages going in opposing directions to pass each other). Most streets are less than 15 feet wide, with the buildings on either side directly abutting the street. There are no true “sidewalks” in Paris beyond the Pont Neuf. Making things worse is the fact that many residents build lean-to sheds or pile wood right on the street in front of their house, in spite of an edict prohibiting this.

Parisian streets are treacherous. Most are unpaved and the dirt is mixed with excrement and other human and animal waste, which gets even worse in the rain. It’s nearly impossible to walk through Paris for any length of time without getting one’s clothes soiled from la boue de Paris, especially if a carriage passes by too quickly.

In addition, pedestrians have to watch out for falling flower pots, as many are precariously balanced on window ledges. Worse still is the waste often flung out of windows onto the streets below. An oblivious pedestrian could easily get showered in urine and excrement.

Even the paved streets aren’t much of an improvement, as they are sloped towards the centre which operates as an open sewer. Some of the waste is carried all the way from the suburbs and into the Seine. Due to the odour and the possibility of staining one’s clothes, men generally let ladies and their betters take the higher road along the edge of the street.

Finally, Parisian streets are busy. Most business is conducted on the street. Open street markets are the norm, where vendors set up temporary booths to hawk their wares. Prostitutes openly proposition clients. City criers also walk the streets announcing products and other information— while the printing presses generate pamphlets, most residents are still illiterate. Showmen entertain passers-by with their antics, and a good showman could effectively block an entire street as a crowd forms to watch.

News

Judging by its multitude of booksellers, Paris has a relatively high literacy rate. Over 80% of men and 60% of women can at least sign their names, and in 1636 the ability to do so is a fair indicator of full literacy. Whether one has time to read is another matter, as only between 10-15% of lower class men and about 30% of servants had books to leave to others upon their deaths.

The official weekly newspaper in Paris is La Gazette, which has been in circulation for five years. It primarily contains information on the nobility and proceedings in the royal court and includes frequent contributions from the King and Cardinal. It is proving to be a quite popular publication and almost every bourgeois household has a current copy on hand.

In spite of the literacy rate and a regular newspaper, most news is still transmitted via a crier, someone who shouts the news while walking through a neighborhood. There are generally two types of criers, the King’s crier and wine criers. The King’s crier is accompanied by trumpeters and, in addition to proclaiming the King’s news, tacks legal notices in busy areas.

The wine criers are also appointed by the Crown and managed by their local municipal officers. They ensure that the municipal tax was paid when a cask of wine is opened. They also make commercial and funeral announcements (many criers are also morticians and have a stranglehold on that trade), as well as making announcements for lost animals or children. Wine criers are not, however, allowed to make official crown announcements.

Carriages

While traveling through the streets of Paris in a carriage is preferable to walking in terms of keeping clothes clean, it does not necessarily mean that you’ll move any faster through the city. In addition, traveling by carriage poses its own set of problems.

Most Parisian streets aren’t designed to accommodate carriages and pedestrian traffic and vendor booths often shrink the street even further. Also, there’s little rhyme or reason to the design of most streets: a carriage could be traveling down a wide street and suddenly find its way barred due to houses up ahead being closer together.

Carriages also have to dodge obstacles, such as woodpiles, showcased merchandise, and even low-hanging signs. Pedestrians are a constant problem, as there is nowhere for most of them to get out of the way beyond a convenient doorway.

With so few wide streets available, those that can accommodate carriage or wagon traffic quickly become congested. As only the Parisian elite can afford private carriages, most vehicles are commercial enterprises and may make frequent stops along the way (with no room to maneuver around) based on their delivery or pick-up schedule. For opposing carriages, right-of-way can spark an argument or even a duel, as it is a great inconvenience to get the horses to turn the carriage around.

In short, carriage travel can slow to a crawl, especially if you’re travelling through an unpaved street in the rain. It doesn’t take much for a carriage wheel to get stuck in the mud or worse.

Buildings

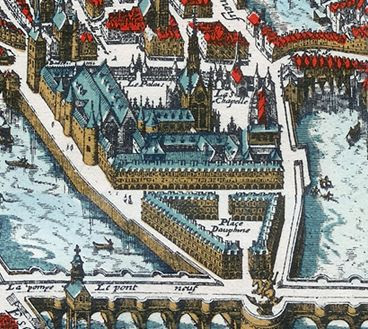

Unless you are attempting to find an easily recognizable building like the Louvre or the Notre Dame cathedral, finding a particular house is no easy task. With the recent exception of the houses along the Pont Notre Dame, none of the houses in Paris have street numbers. A place of business, such as an inn, might have a sign hanging outside, but most homes are identified by street, façade description, or relation to a landmark. Most Parisians are in the habit of asking those nearby where a particular house is located.

The center of activity in any house, rich or poor, is the room with the fireplace. During the colder months, bourgeoisie families gathered in the kitchen to eat and socialize, while nobles could afford multiple chimneys to heat various parts of the house. Shopkeepers often used the front room of their residences to conduct business. Such rooms are unheated and on cold days the shopkeepers continually duck back into the room with the fireplace. Wax candles are expensive in the 17th century. Only wealthy bourgeoisie and nobles use them and then only sparingly. Most candles are made of suet, or animal fat, which gives off an unpleasant smell. Candles and lanterns are not generally lit outside at night unless the occupant is expecting a visitor.

Water

Keeping a home supplied with water is a difficult undertaking in Paris. Most of Paris still doesn’t have plumbing. Only the palaces, schools, monasteries, and wealthy hôtels had access to private aqueducts. Some homes had private wells but these were often so badly contaminated that they were hardly used. Most residents make do by either getting water from the Seine, purchasing it from water sellers, or going to the nearest public fountain.

Public fountains are scattered throughout the city although they don’t resemble the beautiful flowing fountains of private gardens, as Paris’ poor water pressure won’t allow it. Most fountains are simply monuments with taps set around it that trickle water when the handle is turned. Many fountains have places to stand above them, making a fountain a good place for a character to go if he wants to survey the immediate area or meet someone.

Taverns

When not at work or pursuing other obligations, most Parisians like to unwind in a tavern. The King’s Musketeers, for example, have a reputation for strong drinking as they await their next duty. Paris has a notorious reputation for its large number of ales and wines available, and in addition to drinking the Parisian tavern offers meals and a place to mingle. It is also where one can find company for the night as well as participate in brawls over the flimsiest of excuses (such brawls rarely escalate to a duel, unless the participants are gentlemen or nobles). Taverns are barely tolerated by both the church and the government. Taverns have a long-standing reputation for encouraging the loosening of morals, but perhaps more importantly it’s where dissidents can find friendly ears to spread their message or plot acts against the establishment.

Enemies of the Roman Catholic Church and Louis XIII’s rule typically gather here to plot Protestant uprisings, political assassinations, and other traitorous activities.

Taverns generally cater to a particular clientele and quickly establish regular patrons. Thus, when a stranger walks into a tavern it is immediately apparent amongst everyone in the room. They’ll pause their conversations and stare at the stranger until his reason for being here can be ascertained (a King’s Musketeer would rarely walk into a tavern frequented by the Cardinal’s Guard unless he was looking for trouble).

A tavern’s wine stock is also indicative of its clientele. One’s wine preference can mark his home region or where he’s recently spent some time. A tavern with a large selection of wines from Bordeaux and other southwestern wine regions will be frequented by Parisians originally from that area, and Occitan rather than Parisian French is likely the lingua franca. Most of the clientele likely speak in identifiable Occitan dialects and the proprietor is likely a Gascon or Bordelais.

Crime

In addition to the physical challenges of moving through Paris, there are also dangers of a more human nature. Parisian streets tend to be congested, giving pickpockets and cutpurses easy targets (a popular crime at the time is cloak-snatching). A thief can easily rob a pedestrian and fade into the crowd, making them difficult to follow. Some thieves work in tandem with showmen, lifting goods while the victim is enjoying the show. Many showmen are also con men, using their talents to take money from people.

The haphazard layout of city streets makes it easy for pedestrians to get lost. In fact it can be argued that no one in Paris is familiar with all of its streets, only with his immediate neighborhood. This creates a prime opportunity for muggers to follow their prey into a dark alley and waylay him. A common tactic is to direct a victim to a shop, tavern, or whorehouse “just two blocks to your left and down the alley on the right,” and the unfortunate soul thus directed find himself trapped in a blind alley confronting multiple attackers.

Paris becomes even more dangerous at night. There are no street lights, so crime literally can be lurking right around the corner, even on usually safe streets. In addition to the usual muggers, many servants and lackeys prey upon pedestrians to supplement their incomes. Particularly bold criminals might break into a home and rob the owner at knifepoint.

Women, unfortunately, have an even more difficult time walking through Paris. Molestation is common, ranging from unwelcome touching to rape. One type of crime that is committed by impoverished nobles is to kidnap a wealthy young woman, rape her, and then take her to a priest outside the city to be married (the priest is bribed for his services). The woman’s family then owes the noble a dowry. This kidnapping and forcible marrying of young women is surprisingly tolerated in Parisian society.

It’s believed that many of these criminals receive indirect assistance in their crimes. Nobles turn a blind eye towards their lackeys and servants. Criminals often offer the local city guard a cut of their booty.

Policing Paris

In addition to the soldiers that protect the royal palaces (including the King’s Musketeers) and the walls of Paris, there are several other ways in which Paris is policed. The most common way is private security; that is, nobles and wealthy bourgeois homeowners hire their own bodyguards to protect their families and households.

In a less-wealthy neighborhood homeowners may pool their resources to hire guards to patrol the neighborhood (the military forces stationed in Paris already do this, but not to any effective extent beyond major crimes). Poorer neighborhoods police themselves, dragging offenders to the nearest prison and demanding justice.

While most Parisians retire not long after the sun goes down (candles being an expensive luxury), most neighborhoods have night watchmen. These are usually older men or wounded soldiers. Their primary duty is to announce the time, although this is becoming less prominent as many public squares boast at least one public clock and many Parisian homes now sport one.

Night watchmen also call out crimes in progress (most night watchmen carry a large staff that they can bang against stone) to alert the city guard or any able-bodied men that can be called to help (night watchmen rarely confront a violent criminal on their own). Finally, night watchmen escort residents to their homes or offer directions to passersby.

Leisure

There are many opportunities for leisure in the city, providing that a Parisian has the time and livres to indulge in them. The theatre is quite popular and dedicated playhouses such as the Theatre de l’Hôtel de Bourgogne and the Theatre du Marais. Cardinal Richelieu is also building a theatre inside the Palais-Cardinal. In addition to these public theatres many acting troupes perform plays in bourgeois and noble residences, including the Louvre.

There are also several street actors that perform plays on the streets or in the alleys of Paris, essentially begging for donations as they perform. Such performances tend to be bawdier and more risqué than normal and actors run the risk of a visit to prison should they offend the wrong people. On the whole, actors are regarded with suspicion and the church officially considers them sinful, something that the Cardinal is pushing to change.

Tennis, an indoor version of the modern game, is quite popular among Parisian nobility. It is still referred to as “jeu de paume” (palm game) even though racquets have been used for more than a century. In spite of its continued popularity, tennis has already reached its peak in Paris and several indoor courts have been converted to other uses, such as theatres or fencing schools.

The ultimate pastime amongst the nobility is the ball. These social dances are usually held in a noble’s (or wealthy bourgeois’) home. Such balls spare no expense, with nobles saving money all year to host at least one. Balls are generally themed, the most popular being the masquerade ball, in which participants arrive in costume that masks their identity. This gives the attendees license to flirt without consequences, although it also enables non-guests to infiltrate a party more easily (for some nobles, part of the thrill is the danger). Louis XIII also holds several balls in his hunting lodge at Versailles. These “hunting balls” include his fellow huntsmen, their wives, and other guests of the King at the lodge.

For Parisians that can read, there are hundreds of booksellers in the city. Books on a wide variety of topics are available for purchase, including forbidden tracts on Protestantism and the occult (many Protestant tracts are smuggled in from the Netherlands) as well as scientific theories and topics disfavored by the Church. Booksellers generally keep such tracts hidden from view and are only available if the potential buyer asks the right question.

Gambling is common amongst all classes, both with cards and dice. Playing cards have settled into their modern form, although the King is the highest card (the Ace being the lowest). “Jacks” are also known as “Knaves” and all of the court cards have nicknames (the kings being the Biblical David, Charlemagne, Julius Caesar, and Alexander the Great). Tarot cards are also used for playing games.

Animal baiting and killing is also popular. While the lower classes make do with rats and dogfights, royal spectator blood sports include bears, bulls, and lions.

Bonfire parties are also popular, enabling Parisians to carouse through the night with a cheap form of illumination. Several of these bonfires include setting bags of cats afire, adding their screams to the jubilations.

Clothing Styles

Clothing in the 17th Century was fanciful and colourful, and, as always, France led most of the fashions to popularity. Gentlemen (or those who wished to pass for gentlemen) generally wore a doublet or vest, breeches or stockings, boots or shoes, and a hat.

Sleeves were billowy and often slashed to show an inner material, and men's clothing was designed to exaggerated the shoulders and thighs. The collars and gloves of men's clothing were often elaborate, and, towards the end of the Century, ribbons and lace became very popular. Men usually wore their hair to shoulder length, and a moustache and a sort of wispy beard was preferred.

Women in the 17th Century wore uncomfortable corsets and stomachers, and sometimes hoop-like devices called paniers, to enhance their figures according to the then popular mode. Skirts and dresses were worn several at a time, and were often quite long. Sometimes elaborate collars and ruffs were worn, but some fashions favoured a very low neckline. Women's hair was worn in variety of styles. Jewellery and fans were very popular among court ladies, as were 'beauty spots' (small patches placed on the face to cover a blemish, and given names like 'boldness,' 'passion,' and 'coquetry,' depending upon where they were placed).

Hats were popular and elaborate for both sexes, with numerous feathers and plumes. Women, and sometimes men, commonly wore small masks when they went out on windy or unpleasant days, to protect the face. These usually protected only the area around the eyes and the top of the face, but sometimes covered the lower half with a veil. Such masks were often used to disguise one's identity in private situations.

With the rise of the bourgeoisie fashion is becoming an obsession in Paris, as wealthy financiers, doctors, and lawyers find themselves with coin to spend and a desire to emulate the nobility. Those that can afford it often wear several outfits a day, as traveling through the Parisian streets, even in the comfort of a carriage, often soils one’s clothes (and, even if it doesn’t, the fact that you can change your clothes frequently is a sign of wealth and nobility).

Parisian fashion has been heavily influenced by Richelieu’s policies which have banned the importation of gold and silver as Spain, with fresh supplies coming from the New World, had been flooding French markets. Clothiers had to make do with local materials. Embroidery was also curtailed.

Men’s fashion thus became more muted. The welldressed man wears a short cloak or cape over a coat that is slit to show the sleeves and shirt underneath, with breeches that either ended just below the knee or tucked into one’s boots. A soldier would replace the coat with a leather jerkin or buff coat. Heeled boots are popular, especially the bucket-top style that the King’s Musketeers prefer.

The cravat is a recent trend in men’s fashion. Adapted from the scarves worn by Croatian mercenaries drafted into Louis’ army in 1630, the cravat (the term is a corruption of “Croat”), is quickly replacing the ruff. It’s essentially a long scarf tied around the neck and knotted in the front.

Fashionable men wear their hair in long curls and prefer wide mustaches and pointed beards. Hats are becoming shorter and wide-brims, with one side often being pinned up to hold ostrich feathers. Fashion has become slightly freer for women, as heavier fabrics have enabled them to do away with layers.

The well-dressed woman wears a dress with a looser bodice and more open neckline. The farthingale has fallen out of style, replaced by padding to enlarge skirt lines. Bourgeoisie women often wear hats similar to the men.

Food

As the cultural and political capital of France, Paris is a cosmopolitan city. Local and provincial dishes can be found in many taverns across the city as well as foods imported from other countries in Europe and the rest of the world. A traveller to Paris from other parts of France should be able to find taverns and restaurants with familiar dishes on the menu. Travelers from other European places such as England, Flanders, Lombard, and Tuscany should also have little trouble finding tastes from home.

From the New World come new foodstuffs such as turkeys, corn, and potatoes. The popular provincial dish of cassoulet (a bean stew supplemented with meat) owes its origin to the haricot bean.

Conversely, many modern dishes and techniques associated with France have yet to be developed in 1636. Bread-thickened sauces are still the most popular, as the béchamel sauce, bisque, and roux have yet to be created. The croissant, today a ubiquitous French staple, is still a good two centuries away.

By 1636, the tables of aristocrats and commoners alike were adorned with plates and eating utensils (fork, knife, and spoon). Wooden utensils were the cheapest and many families passed more expensive plates and silverware down from generation to generation. The typical Parisian table typically includes fruits, meat, cheese, and/or seafood. Vegetables except for artichokes and truffles are generally shunned unless well-boiled.

Soup is a popular dish; it is an adaptation of English pottage (soup is so-named for the "sop," or bread, placed at the bottom of the bowl). Wealthy tables make elaborate presentations out of food. One of the most popular is the gilded swan or peacock, which is presented at table with all of its feathers intact and its beak and feet gilded with gold or silver. Inside, the swan was stuffed with a minced meat made from a tastier bird such as a chicken. While wine is still the preferred drink at the Parisian table and tea is still a few decades away, both coffee and hot cocoa are making inroads at the Parisian table.

Names and Forms of Address

First names in 17th Century France, and in most of Catholic Europe at the time, were taken from the names of the Saints. Often a child was named for the patron Saint of the day on which he was born or baptized. Huguenot names were usually taken from the bible.

Last names were taken from one's parents, but could be substituted, by Nobility, by the title of an estate owned. Nobility could add as many estates on to the end of their names as they owned, each normally preceded by 'de' ('of'). Thus a Baron who owned estates in Cahores, Albi, and Castres, could call himself 'Baron de Cahores d'Albi de Castres, but he might wish to be modest, and just be known as 'Baron de Cahores' or 'Baron d'Albi,' etc.

Sometimes, gentlemen took on 'Noms du Guerre' ('Names of War') when they entered the service, to disguise their real identities. Such names wher also sometimes given as nicknames. They tended to be short, with no last name or title added, The names 'Porthos,' 'Athos,' and 'Aramis' in 'The Three Musketeers' were all noms du guerre used by the adventurous trio for various reasons.

Characters who hold a Title or position in a hierarchy will often be addressed as 'Monsieur le. . . ' whatever. For example, a Captain might be referred to as 'Monsieur le Captain' or the Baron discussed above might be addressed as 'Monsieur le Baron de Cahores d'Albi, etc ' This is a show of respect towards the person addressed. If a character addresses a person 6 or more Social Ranks above him, he should use 'M'Lord' or 'M' Lady' (equivalent to 'Signeur'or 'Signeure') to show respect. The King of France is allowed to speak of himself in the first person plural ('nous' form) - Le. the King might say 'We are feeling quite good today,' and be referring only to himself.

Everyday Life

Everyday life in 17th Century France was in many ways, like it is today. The 17th Century was a period precariously balanced, however, between the enlightenment of the scientific era and the barbarism of the middle ages. Scientific thought was becoming widespread among the intellectual circles of Europe, and many new Universities and Academies were founded, but this was clouded by constant wars and internal conflict, and the desperate poverty of the lower classes, For gentleman, however, there was always time for amusement in many forms. Gambling, with cards, cocks, and dice was very popular. For recreation, one could fence, or perhaps play tennis. Social events also were always available to a young man of means, including balls, performances of music, opera, drama, and comedy. Amusement took other forms as well, and morals were often lacking in relationships.

Mistresses for men where common, as was infidelity by wives, husbands, and, indeed, mistresses. Illicit relationships were so common that many Clergymen also had mistresses, and occasionally fought duels over them.

It was also a time when enlightenment and superstition stood side by side. While Philosophers and Scientists discovered more and more about physics, mathematics, chemistry, and astronomy, the common people were enchanted by fortune-tellers, prophets, and alchemists. It was a time of many contrasts.

Art in France during the 17th Century was dominated by the upper classes, who constantly wished to have their portraits done. The Baroque fashion perhaps hit its height in this era. A monument to the extravagance of the nobility was the Palace at Versailles, built by Louis XIV in order to awe domestic nobility and foreign monarchs alike. The styles of the upper classes were full of gold leaf, silver trim, mirrored glass, marble fountains, and manicured gardens, with no room for restraint.

Transportation also became elaborate for French elite. A common man might have to walk or ride from place to place, but any man of wealth and position either rode in a carriage, or was carried by servants in a palanquin. Carriages were often thoroughly decorated, and usually had a primitive system of shock absorption, so as to make the ride a pleasant one. Teams of as many as 16 horses were set to pull carriage's. This did not enhance the speed noticeably, but it did serve to impress one's fellows.

Life for the Peasant in the 17th Century was hard, and similar to his situation in the middle ages. France was still Feudal in many ways. A typical peasant wore old clothes, and wooden shoes. He ate poorly, worked hard, and died fairly young. More opportunity for social advancement was possible than in previous times, though, because of the rise of the Merchant class, who were common born, but had money. For the industrious and clever, the newly opening industries of banking and world commerce allowed great chances for advancement.

Religion

Religion in the 17th Century was complicated. Religious wars had wracked France in the 16th Century, only to be repeated in the 17th. Most French in this period were Roman Catholic, but a small minority were Calvinist Protestants, known as Huguenots. In 1598, King Henry IV of France signed the Edict of Nantes, protecting the Huguenots, but this was often disregarded in the 17th Century, as the Protestants were persecuted by Cardinal Richelieu, and was finally revoked by King Louis XIV. Huguenots often held positions of power and wealth, however, and were occasionally aided by the English to their struggles with the Catholics.

The rest of Europe was a patchwork of religions. Spain, Portugal, and the Italian States were bastions of Roman Catholicism. The Holy Roman Empire (Germany) was split heavily between Catholics, Calvinists, and Lutherans, as was Poland. Sweden and Denmark were staunchly Lutheran, and England, of course, was predominantly Anglican. Switzerland was mostly Calvinist (especially in the German areas) and the United Provinces (The Free Netherlands) and Scotland were split between Catholics and Calvinists. The Russias (an emerging power at this time) were almost completely Greek Orthodox. The Ottoman Empire was Moslem, with a small Greek Orthodox minority (mostly in Greece), Religion was the cause (or at least the excuse) of many international disputes, but power was the guiding force which led to most wars. The Thirty Years' War exemplifies this, in that Protestant and Catholic forces were found in great numbers on both sides.

The French Military

The 17th Century was a significant time for the French Military, and it heralded many of the changes that lead to modern armies. At the beginning of the 17th Century, all the armies of Europe were inefficient and disorganized. Ranks were commonly bought, and were often given to high-level noblemen with no practical experience. This started to change, however, under the rules of King Louis Xlll and Louis XIV.

Courts and Justice

Justice in the 17th Century was rather hard to come by, and many barbaric laws and punishments lived on from the Middle Ages. Minor crimes of which one might be accused included: theft, robbery, burglary, forgery, and harlotry. More dangerous crimes were murder, assault, arson, and heresy. Perhaps the worst crime imaginable was treason.

The city guards (and the Cardinal's Guards in Paris) often served as police, and were usually disorganized, prejudiced, and unjust. Protection was erratic and subject to bribes. It was quite easy for a Magistrate to have an enemy arrested on false charges and kept in prison for a length of time without a trial.

When a trial occurred, 'justice' was usually meted out swiftly and violently.

Military Justice

Military justice in the French army of the 17th Century was similar to civil justice. Soldiers, however, were usually subject only to Military law, and might avoid trials for minor crimes, in favour of a military punishment for a similar offense (usually coming under the title 'impeding military efficiency').

Minor offenses within the military are dealt with by a single Officer of higher rank than the offender. These offenses might include (as mentioned above) 'impending military efficiency,' failure to report for duty, and military fraud. Punishment was usually a short term in the stockade (2 or 12 days), or, for blatant situations, loss of a Rank or special position.

Major offenses were tried in a Court-Martial by a Tribunal of Officers, Martial Magistrates. Roll for the results as for a normal trial. Major Offenses and their punishments were: Mutiny or Rebellion (Life imprisonment or Death), Desertion (Loss of all Rank, and I to 6 months imprisonment), and Treason (Offender is Broken on the Wheel, as listed above.

Generals and the Field Marechal may only be tried for Treason, and must be tried in a normal court, by a tribunal made up of the Minister of Justice, the Minister of War, and the Constable General.